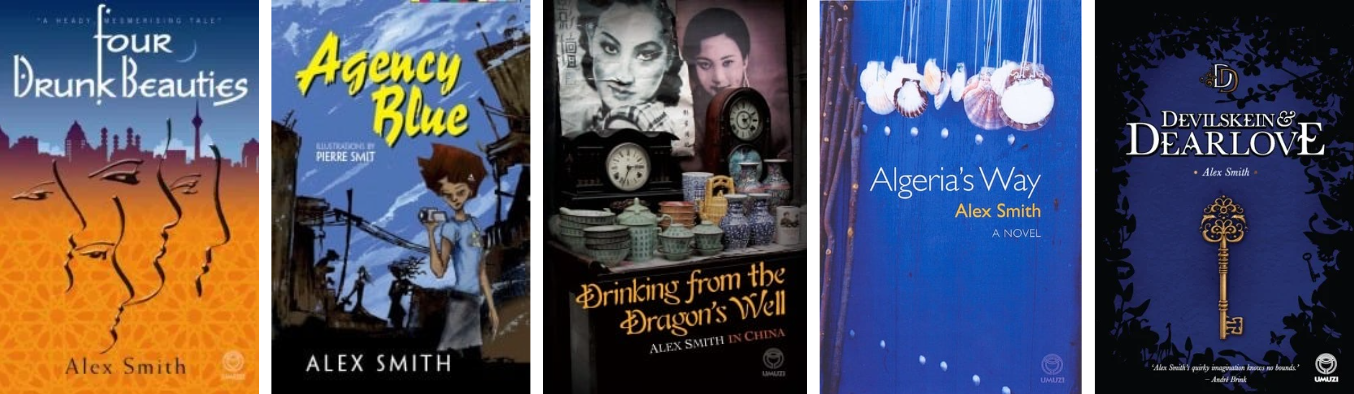

Alex Smith has penned an array of literary works, including two magic realist novels, Algeria’s Way and Four Drunk Beauties, alongside two YA fantasies, Agency Blue and Devilskein & Dearlove. Her memoir, Drinking from the Dragon’s Well, offers a compelling glimpse into her experiences teaching English in Wuhan, China.

Alex’s short stories have appeared in journals and anthologies across the globe, while her middle-grade novels, translated into African languages and used as set works in South African schools, showcase her broad appeal.

Alex has garnered prestigious awards, including the Nielsen Booksellers Choice Award and the Sanlam Youth Literature Award. She was shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing and was a finalist in the NLDTF/PANSA Festival of Contemporary Theatre Readings.

Endorsed by acclaimed author Andre Brink, Alex was selected as a candidate in the Rolex Mentor & Protégé Arts Initiative, solidifying her status in the literary realm.

In addition to her writing accomplishments, Alex has shared her expertise as a beloved tutor at the Writers College for over fifteen years, guiding aspiring writers through the intricacies of writing short stories, novels and memoirs.

We asked Alex to share her experience as a writer.

What inspired you to start writing fiction, and how has that initial spark evolved over the course of your career?

Acting was probably what led me to writing. I did drama as a school subject, and the plays of Shakespeare and Chekhov and the comedies of Noel Coward made me love words.

In high school, we studied An Actor Prepares, Constantin Stanislavski’s iconic method acting text. Method acting is quite close to writing – you want to go beyond creating a caricature and actually become the person, and when you write, you definitely need to put yourself into your character.

I really wanted to be an actress as a teenager. But my wise aunt, who was a writer, said, ‘Unless you can’t live without acting, don’t choose it as a career; it is too harsh and heartbreaking.’ So I studied business science and psychology instead of acting at university.

But while sobbing through economics, I found that writing a novel is a bit like staging one’s own imaginary play – you get to be all the actors plus the set and sound designer. So without acting in my life, I turned more to writing.

While working my first job, I wanted to write a novel about computer programmers. True to the method acting approach, I signed up to study computer science. That novel never saw the light of day, but the computer studies have been utterly invaluable ever since.

For a time, I gave up on the idea of a creative career and worked in marketing, which afforded many travel experiences, but was somewhat soul-destroying.

Finally, I realised I couldn’t live without writing. So I quit the day job (actually a very bad idea, and I would never advise this extreme approach!), did the Camino de Santiago in Spain and then signed up for a creative writing masters at the University of Cape Town.

And guess what? My dissertation novel was set in Spain, and it was the first novel I had published by Penguin Random House in South Africa.

Can you share a bit about your creative process? How do you typically approach crafting characters, plotlines and settings?

Haphazardly.

I do it differently for different books. It depends on whether it’s something that has simply come to me or if it needs to fit a particular brief because it’s been commissioned or is for a competition.

Creating some kind of plot plan is quite useful, and I always recommend this to my students.

Setting is often what inspires me first – so the place is integral to the whole story and the characters in it. I’ve always had a passion for travelling. At 15, I wrote my first novel, set on the island of Mauritius. Naturally, it was dire. But in terms of how that spark has evolved, place is always a powerful element in the stories I choose to write.

Many aspiring authors struggle with writer’s block. Have you encountered this challenge, and if so, how do you overcome it?

Writer’s Block is vilified, but sometimes it’s better not to write. Like fields need fallow periods to regenerate, so creative people need times when they’re absorbing rather than producing.

In writing groups, people often say you should write every day. Well, I don’t agree with this. You should write when you need to – when it brings you creative joy or there’s a story you’re burning to tell, when you’re earning a degree or being paid.

If you’ve been commissioned to write something, you probably won’t be bothered by writer’s block, you’ll just get it written (or lose your job and find another line of work).

Just wanting to write is not the same as needing to write, and I suppose writer’s block arises when you want to write but don’t need to.

Your work has been recognised with prestigious awards. How did you navigate the balance between artistic integrity and meeting the expectations of readers and critics?

Not very well. I didn’t focus much on anyone’s expectations and just wrote what I felt like writing, which was great from a creative point of view, but a bit of a marketing nightmare.

Every book has a different target market, and that’s not ideal for creating a loyal readership. However, I’m not sure I would change what I did in the past. Going forward, I feel I should be more strategic and possibly select a genre to focus on!

Collaboration is often key in the publishing industry. Can you discuss your experiences working with editors, agents and other professionals in bringing your stories to life?

I’ve worked with some wonderful publishers and editors, and it’s an exacting and challenging but immeasurably satisfying process to take a novel through the final drafts with a professional editor.

Friendly readers are great, but nothing compares to a thorough edit. It’s like having your friend cut your hair versus going to a proper stylist – they’re working with the same head of hair, but the results can be markedly different.

Your writing often delves into complex themes and emotions. How do you ensure authenticity and depth in portraying these elements?

I observe and talk to a lot of people, and I really like to listen; I’m curious about how different people experience the same thing. Three years of undergraduate psychology and an honours course in criminology were a good foundation for getting an insight into social science, people, function and dysfunction.

At the moment, I’m teaching English to teenagers from Europe and, while I hope they’re learning a lot of English from me, I find I’m learning so much from them. Their perspectives are refreshing, even though their tendency to spend hours each day scrolling on TikTok is concerning (and I wonder how it will impact on the future of novel-length works).

In terms of being authentic, I just try to understand, and that can mean peeling away layers to uncover what lies beneath a particular action or reaction.

In today’s rapidly changing literary landscape, how do you strive to create enduring stories?

I’ve never thought about it that way. In my opinion, it’s mostly chance and luck if something endures. Most novels have a very short shelf life, and that’s a reality of the commercial side of books. Some stories strike a chord with many people, which is possibly a reflection of good timing.

I don’t strive to create enduring stories. I strive to create; the medium I’ve developed more skill with than any other is words. I like drawing, too, and acting, cooking and singing (for a short time I wanted to be an opera singer like Maria Callas – and even made it to the top 100 in SA Idols!). But as it turns out, I’m better at playing with words than with watercolours.

What advice would you give to aspiring fiction authors who are navigating the challenges of breaking into the publishing industry?

When you feel you really have something you want to write, then write it. Understand that a first draft is not the completed story, and don’t underestimate the importance of multiple drafts – if you do, you will be disappointed.

Sometimes, debut writers imagine that having written the last page of their first draft is the end of the writing process. Well, that’s simply wrong and is likely to result in much rejection and heartache.

Enrolling in a course with a professional reader looking at your text can be very useful. Having multiple readers or getting a reader report from an editor or writing institution is also a good way to see how you can develop your story from draft to draft.

Your capacity to respond to editorial feedback is probably what will determine your success as a published writer. There’s a fine balance between staying true to your vision and being responsive to useful critique – but know that not all critique is useful; only your instincts can guide you as to which to heed and which to ignore.

When you approach publishers and agents, it helps to have a publishing track record – short fiction is a good place to start. Social media presence is also powerful – if you have a tribe of followers, you have a tribe of potential readers and book buyers. This will stand you in good stead whether you’re approaching a traditional trade publisher or considering self-publishing.

Be modest with your expectations.

Looking ahead, what future projects or themes are you excited to explore in your writing?

I’ve recently moved to Ireland, and because countries and cultures are often a big part of the stories I like to write, Ireland will definitely feature strongly in my next projects. At the moment, I’m counting clovers and soaking up the meadows and medieval towns.